Independence Day

I will always be a reluctant widow, but at times, I am also a grateful one. To have my husband’s family in my life, years after his death, is a gift beyond measure. I had the deep honor and pleasure of spending the day with Bob’s whole family in St. James on Sunday, something we haven’t done in far too long. His parents still live there; his sister, Nancy and her family who live in Billings, MT and Colorado, were home for their annual summer visit.

I find it a curious and grace-filled thing, to still be connected to Bob’s family long after his death. Curious, because for most of my marriage, I held tight to so many hangups regarding my place in his family; as such, I maintained a guarded distance between us. This wasn’t a conscious choice on my behalf and it had nothing to do with Bob’s family personally. Back then, much of the world was so bewildering to me, I didn’t know how to simply be; as such, I kept safe space between myself and nearly everyone and everything I encountered, Bob’s family included. Erecting barriers was a coping strategy I’d developed at a young age, to manage a world that often felt confusing, unsafe and unpredictable, for a host of reasons. That’s not to say I lived a life completely in fear, but I certainly lived within tight perimeters which gave me a false sense of control.

Grace-filled, because things could have ended so differently. Death often arrives with the force of an earthquake, shattering entire families to pieces. I know women who no longer have contact with their deceased partner’s family, their relationships permanently destroyed. But, recently, I’ve been wondering, is death itself the destructive element? Or is it unchecked forces within us, that have the potential to shake, rattle and upend our worlds?

Carl Jung once said, “until you make the unconscious conscious, it will continue to rule your life, and you will call it fate.” There is legitimate history behind the thoughts and actions that ruled my younger years. At the time, I didn’t have words for it, didn’t know how to describe it, much less sit with my feelings and gently questioning the reasons for them. God forbid, would I ask for help to alchemize them into something more expansive and true. I simply didn’t know how to. Instead, I berated myself, over and over, for being “that way” in the first place, wondering why everyone else seemed to know how to live without the heavy load I was burdened with. It takes excruciatingly hard, terrifying work to excavate the deeper truths that exist far beyond the thin veneer of our presented lives; it’s even more difficult to hold these truths gently in our own hands, anoint them with holy words, or paint strokes, or a melody, and transform them into something of the sublime. It is sacred work, necessary work, psychologists will call it trauma-informed work, and it cannot be done in isolation. That’s not to say we don’t often try to go it alone—many of us do, not realizing there might be a different, kinder, more loving way. And by “we,” I always, only ever mean me.

Bob’s home life was strong, stable, reliable—the encyclopedic definition of the All American Family, complete with legendary white house and picket fence. By contrast, my home life was precarious, unpredictable, always in crisis or at the very least, in constant chaos. That’s not to say his family was perfect, I think they’d be the first to emphatically renounce such a claim. That’s not to say that mine was void of love or support—that is also not true. Still, the disparity between our respective families of origin intimidated the hell out of me. I knew exactly how to operate in crisis because I was raised in in—I became the New Houdini, developing all kinds ways, novel and otherwise, to escape. But how to react in a home that was overflowing with genuine love, support, respect, without impossibly arbitrary, unspoken conditions? That, I had no idea how to manage. It made me anxious af, as the kids say.

Curious, how normalized dysfunction can be, how one can grow so comfortable in the heat of chaos than in the lack thereof. And by comfortable, I simply mean that there is safety in the familiar. I don’t know that I’ve ever been comfortable in m own skin. In my family, we lived in a constant state of waiting for the other shoe to drop, you’d think we were a family of octopuses, so many shoes dropping at any given point (If you’re wondering about the etymology of octopus and its plural variations, btw, here you go, you’re welcome: https://oceanconservancy.org/blog/2022/02/01/plural-octopus/#:~:text=Octopuses%20✅&text=Generally,%20when%20a%20noun%20enters,this%20is%20the%20preferred%20plural)

In 2009, Bob was diagnosed with osteosarcoma (a rare bone cancer). This was his second cancer rodeo—he’d battled Hodgkin’s lymphoma as a boy—which made me realize that all these years, Bob’s family was quietly living their own version of waiting for the other shoe to drop: if and when would cancer return? Would it be as bad as the first time? Worse? When Bob got sick, all of our worlds—mine, Bob’s parents’, his sister’s, her family’s—were upended in deeply dramatic, traumatic ways. I was suddenly shoved into the role of caregiver/advocate—to say I was wholly inadequately prepared for such a shitshow couldn’t be any less understated. To say I felt like I failed at the job in the worst of ways doesn’t even begin to cover it. That I didn’t do enough to help him. That I should have known how to advocate for him better than I did. That I could have protected him from the suffering that he endured. That I should have somehow, single-handedly, been able to put a stop to the brutal experience. That I should have done this, that I shouldn’t have done that…to say that I carried this heavy load of pain, guilt, shame and loneliness with me for far too long is a gross understatement. After a brutal, valiant battle, Bob died in our home on May 3, 2011.

Shortly after Bob died, I was visiting his parents one weekend, as I did often back then. Jim told me that Bob’s headstone was done and was in place at his grave site. He asked if I wanted to see it. With knots in my stomach, I agreed. We drove out to the cemetery. Jim parked the van. I glanced out the window. I saw my husband’s name etched into charcoal granite. I saw his birth date, then death date carved in stone—you know when we say “carved in stone,” we mean it permanently, right? To see that date leveled me. More evidence that his absence was permanent. He was never coming back. I folded over my legs and began sobbing into my knees (did I ever stop crying those early days, I often wonder, it felt like that’s all I did for days, weeks, months). Jim quickly threw the van into drive. He left the cemetery in a hurry, apologizing profusely all the way home. Jim later told me that he visited the gravestone on the daily in those early years; perhaps he still does. I never went back.

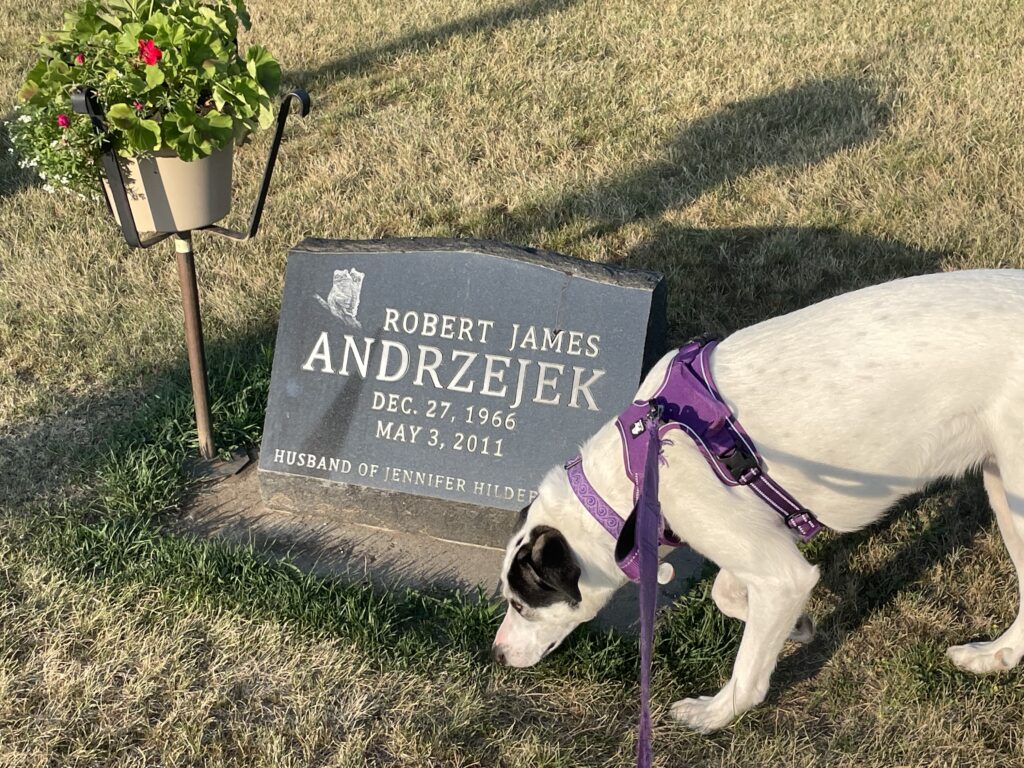

Until this past weekend. After my long, lovely visit with Bob’s family on Sunday, I took Lucy to the dog park on my way out of town. The dog park is on the same end of town as the cemetery. After Lucy did her doodie (haha, I’m hilarious), we got back into my car and by sketchy memory, I found my way to the cemetery at the edge of town. “Holy shit,” I thought, “it’s so much bigger than I remembered.” I eased down the gravel drive, between clusters of gravestones. I remember his being at the very far end of the cemetery. I kept driving til I came to the last row. I turned in. My eyes scanned the line of headstones until they stopped at ANDRZEJEK carved into black granite in large capital letters.

I parked the car, kept it running to keep Lucy cool. I got out and began walking across the lawn. I took long, slow deep breaths with every step. I walked to the slab of black granite and stood in front of it. I read his name out loud: Robert James Andrzejek. I read the two dates below his name—December 27, 1966 and May 3, 2011. I gazed at the etching of the baby great horned owls up in the lefthand corner—replicated from a photograph that Bob had taken of a pair of nesting owls found in our back yard, the first spring when he was sick. All those things I remembered from that first visit so long ago. But this time, I saw something else. A row of words stretched across the bottom of the stone: “Husband of Jennifer Hildebrandt.” I was stunned. I don’t remember seeing these words before. I felt tears slide down my cheeks as I slowly slid down to kneel in the grass. My fingertips ran across the letters.

I also have a memory of both Penny and Jim’s names flanking Bob’s name on the stone, as well, but they were missing. I was confused. Was this a new headstone? Still crying, I pulled out my phone and called Penny.

“Hey Jen, is everything okay?”

“Yes, everything’s okay—I mean, I’m at the cemetery, visiting Bob’s grave, I haven’t been back here since Bob’s headstone was put in—first of all, I could swear yours and Jim’s names were also on the headstone—am I not remembering that right?” I asked.

“Oh GOD, no,” she exclaimed, “I’m not putting my name or date on anything yet—I don’t want anyone to know how old I am until after I’m long gone,” she burst out laughing.

I was laughing and crying at the same time. “I also don’t remember the last line on the stone,” I said, “it reads ‘husband of Jennifer Hildebrandt’—was that always there?”

“Oh yes, of course, that’s been there right from the start. We were so happy to have you as a daughter in law, Jen, and we’re still so happy to have you in our lives, I hope you never forget that.” I started crying harder, thinking how hard I’ve made my life sometimes, yet how some people have the capacity to see through the cracks in the walls I’d worked so hard to build, and have never bailed, even in the hardest of times. “Thank you so much for that,” I said, “I’m honored to have you all still in my life, I’m so happy I came down today.”

As I stood up, I felt another weight from the past twelve years slide off my shoulders and pool at my feet. I stepped over the rumpled pile, watched it seep into the ground, then made my way back to the car. xo.